This is a thread to talk about a storytelling

The Storytelling Thread

Home » Forums » Movies, TV and other media » The Storytelling Thread

- This topic has 998 replies, 24 voices, and was last updated 4 years, 5 months ago by

Anonymous.

-

JasonParticipantMay 30, 2021 at 8:22 pm #65126

JasonParticipantMay 30, 2021 at 8:22 pm #65126To be honest though the vast majority of time travel stories have logic issues to a greater or lesser extent. The Terminator franchise that you mentioned is far from consistent, and actively switches from a closed-loop approach to the timeline in the first movie to a split-timeline “the future is not set” approach in the second.

Have you seen Tenet?

I have it on my DVR, and I think I’ve re-watched certain parts about thirty times trying to parse out all of the forward/backward stuff going on. That building that gets blown up at the end is maddening, as is the broken car mirror, and how those inverted bullets work…

-

Dave

Moderator -

JonParticipantMay 30, 2021 at 11:07 pm #65135

JonParticipantMay 30, 2021 at 11:07 pm #65135and how those inverted bullets work…

Hint: They don’t, so don’t bother =P

-

Al-xParticipantMay 30, 2021 at 11:13 pm #65136

Al-xParticipantMay 30, 2021 at 11:13 pm #65136Also from that link… about Raiders:

If for some reason you haven’t seen Raiders of the Lost Ark, well, stop reading things on the Internet and go spend two hours with the greatest adventure movie of all time. The internet isn’t going anywhere. OK, remember how the entire movie is about world-renowned adventurer and actually pretty terrible archaeologist Indiana Jones trying to recover the Ark of the Covenant from the Nazis? And remember how in the end, when Belloq and his Third Reich associates open up the Ark, the vengeful spirits within come out and kill all the Nazis by literally melting the flesh off their bones? You should remember that; it’s pretty great and one of the most memorable Nazi-melting movie moments ever filmed.

But here’s the thing: The only reason Belloq and the Nazis do that ceremony out in the desert instead of in the heart of Nazi Germany is because Indy himself destroys the airplane that was going to transport the Ark back to the Fuhrer. If he hadn’t, Belloq would’ve opened the Ark back in Berlin, where Hitler himself — and likely the rest of the Nazi high command — would’ve been present to be melted along with everyone else. Considering Raiders takes place in 1936, Indy’s involvement kept World War II from ending nine years earlier than it actually did.

Read More: https://www.grunge.com/102584/one-messed-thing-80s-movies-nobody-talks/?utm_campaign=clip

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Al-xParticipantMay 31, 2021 at 12:04 am #65138

Al-xParticipantMay 31, 2021 at 12:04 am #65138A listing of super hero moments that made no sense:

https://www.buzzfeed.com/evelinamedina/nonsense-superhero-movie-moments

-

Al-xParticipantJune 1, 2021 at 2:31 pm #65271

Al-xParticipantJune 1, 2021 at 2:31 pm #652712 users thanked author for this post.

-

Al-xParticipantJune 12, 2021 at 7:04 pm #66488

Al-xParticipantJune 12, 2021 at 7:04 pm #66488Casting

Angelina Jolie’s latest movie has her as a fire fighter. Thing is, as one member posted here, no one could really buy into her being a fire fighter, as “one of the boys”.

Reminds me of this movie years ago that had a young hot Michelle Pfieffer as a lonely, down on her luck waitress. There was a scene that had her on a Friday night walking home alone with a box of pizza in an apartment that is hard to imagine being in on a waitress’

salary – tips and all.There have been miscasts (like Travolta as a cowboy) where the studio thought to get the hottest star at the time in whether or not they can really do the story justice. Nowadays, studios are even shoehorning actors who just have the pretty look or connection, like Clint Eastwood’s son Scott, thinking that their presence alone will make up for plot weaknesses.

It messes up the story.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

JRCarterParticipant

JRCarterParticipant -

Dave

Moderator -

Anonymous

InactiveJune 12, 2021 at 8:00 pm #66496Reminds me of this movie years ago that had a young hot Michelle Pfieffer as a lonely, down on her luck waitress. There was a scene that had her on a Friday night walking home alone with a box of pizza in an apartment that is hard to imagine being in on a waitress’ salary – tips and all.

If that was FRANKIE AND JOHNNY with Al Pacino as her co-star, it was based on the play Frankie and Johnny in the Claire de Lune where Kathy Bates played the role across from F. Murray Abraham. I remember a lot of critics at the time pointing out that it was a little difficult to buy Pfeiffer in the same role basically written for Bates, but the entire play was rewritten for the screen so they had to change a lot. In the end, it was pretty successful.

Casting is tough, and it is hard to sell a lot of actors to the money people for the movie because the filmmakers are trying to make the best movie or television show while the people financing only care about how many people an actor can attract to see it. So, they can’t just argue that an actor can do the best job in the role, but that they can get people to see a movie. So you might have an actor lined up and ready for production, but then a television or movie they were just in flops, and suddenly you have to recast because they aren’t bankable in the eyes of the investors.

Or a talent agency has packaged up the whole thing or could be losing their clients work because they want them available on another packaged product that might not even happen, so you can’t even get to offer them the role. It’s a f–ed up business that has always been f–ed up but changes so that it’s just f–ed up in different ways – especially for actors.

However, as far as audiences, it doesn’t really make much difference. The World Is Not Enough made the most of any Bond movie before it and Frankie and Johnny was a modest hit as well critically and financially. Michelle Pfeiffer was even nominated for a Golden Globe (or was it an Oscar?). Audiences don’t care and critics don’t really care that much either. URBAN COWBOY was a hit at the time, and really it was pitched more as SATURDAY NIGHT FEVER for Country Music and that’s why Travolta got the role. The primary problems with THOSE WHO WISH ME DEAD aren’t with the casting, but more to do with the by-the-numbers thriller plot from the writer director Sheridan who really came to prominence by not doing things by the numbers.

Still, I’ve seen plenty of positive reviews for it regardless, and the casting isn’t that out of place based on Jolie’s previous roles, LARA CROFT, MR & MRS SMITH and SALT, for example. The main difference is that those were popcorn movies while people going to see it for Sheridan rather than Jolie were not really into that. Like if you went planning to see SICARIO and instead they played DIE HARD.

-

Al-xParticipantJune 13, 2021 at 9:38 pm #66590

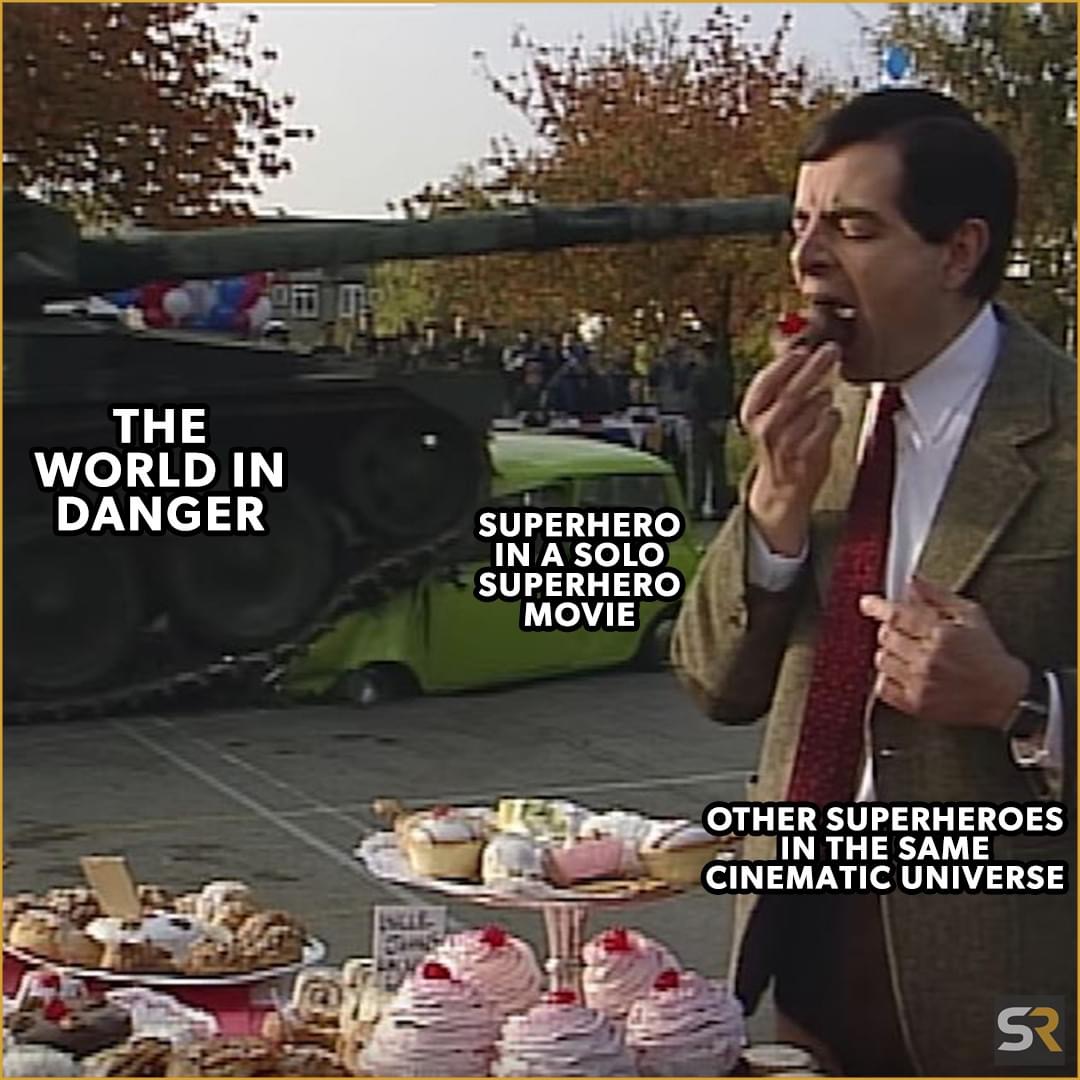

Al-xParticipantJune 13, 2021 at 9:38 pm #66590With those solo SH movies in a shared movie universe: There should be a small passing reference that the other heroes are away on a beach vacation or something…

In comics, in Kingdom Come, Mark Waid deliberately made Martian Manhunter mentally out of it so that he wouldn’t be able to tip the scales leaving only Superman and Captain Marvel the most powerful two.

In DKR, Frank Miller briefly explained how the rest of the JLA went their separate ways and out of the picture, so everything was held at a constant leaving only Bats and Supes in the end.

-

JonParticipant

JonParticipant -

Anonymous

InactiveJune 15, 2021 at 7:06 pm #66771Rewatching the first couple seasons of the SOPRANOS. Also watched a few episodes of BOARDWALK EMPIRE. I never really liked the latter series while I can easily enjoy rewatching the former. I think it’s because the SOPRANOS is essentially a comedy – a very dark comedy – with dramatic elements and the interplay works either way. While the few comic elements of BOARDWALK EMPIRE usually aren’t very funny and its dramatic elements are surrounded by a lot of pretentious dialog. Only a few of the actors really sold their characters in Boardwalk, while it is hard to separate the actors and the characters in SOPRANOS. It’s actually a little jarring to see interviews with James Gandolfini and realize his voice and manner are very different from Tony or most of the characters he played in movies as well.

-

njerryParticipantJune 15, 2021 at 9:55 pm #66789

njerryParticipantJune 15, 2021 at 9:55 pm #66789I loved BOARDWALK EMPIRE, partly because I’m a sucker for period dramas, but mainly because of the performances of so many cast members — Steve Buscemi, Shea Whigham, Michael Shannon, Kelly McDonald, Stephen Graham, Michael Kenneth Williams, and Bobby Cannavale, just to name a few. I loved how fictional or composite characters (“Nucky Thompson” was based on real-life Atlantic City figure Enoch Johnson) interacted with real characters like Lucky Luciano and Al Capone. It ended too abruptly, but up to that point it was a riveting story.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJune 16, 2021 at 2:11 am #66809That is a good point. It did seem to peter out rather than really reach a satisfying conclusion. However, though I can see why people liked it, I can also see it was a fairly unbalanced series which is why it hasn’t had the longevity of Sopranos – which had a similar massive cast of characters and an equal amount of repugnant behavior. It didn’t feel like the writers or the actors really hit their groove with Boardwalk Empire while the Sopranos pretty much got it right out of the gate and I think a lot of that was that Sopranos kept its characters grounded in the situation.

-

njerryParticipant

njerryParticipant -

Al-xParticipantJune 17, 2021 at 9:37 pm #67002

Al-xParticipantJune 17, 2021 at 9:37 pm #67002Movies with bad endings:

-

Al-xParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 3:02 am #67650

Al-xParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 3:02 am #67650Plot armor

I first heard this term in the old MW Game of Thrones thread. Some of the characters were guaranteed to be there the last season so you knew they would survive whatever came.

Like Indiana Jones’ hat. 😂

The problem is It does take away from the unpredictability of a show that takes itself seriously.

Or in comics- I recently read the gist of this latest Marvel event of the Squadron Supreme. In the crossover issues, a LOT of formidable teams that opposed them (even Galactus, Watcher, Thanos with the gauntlet, Phoenix..) went down way too fast in their fights.

Only (you guessed it) the remnants of the Avengers defeated them in the end and restored the timeline.

The plot armor was the SS team mowing through everyone without any casualties until the end.It is all fixed. As if it is fiction. But the fact that it looks so fake and contrived takes away from the overall story.

Bad storytelling.

-

This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by

Al-x.

Al-x.

-

This reply was modified 4 years, 6 months ago by

-

Al-xParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 1:38 pm #67680

Al-xParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 1:38 pm #67680Speaking of GoT, this is what GRRM says now about the last season. He never thought the show would catch up with him:

https://www.buzzfeed.com/alexgurley/george-rr-martin-got-issue

-

DavidMParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 2:35 pm #67690

DavidMParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 2:35 pm #67690The thing about plot armour is that it’s not just that the hero survives, but it’s that he survives stupid things that *should* kill him.

We know that the hero is going to face minor threats along the way, and we know that he’s going to win. There’s nothing wrong with that, it’s basic storytelling. If the hero went from “Here’s the quest” to “Now fight the big boss” with nothing inbetween then you’d not only have a very short book, you’d also have no opportunity to learn about the hero and watch him grow. That’s what all the intervening threats are there to do, and we know that so we don’t expect him to die.

But it doesn’t work if the threat is so extreme that there’s no way the hero should survive it. As soon as that happens, we see the plot armour for what it is and the book loses credibility.

-

ToddParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 3:32 pm #67700

ToddParticipantJune 25, 2021 at 3:32 pm #67700Speaking of GoT, this is what GRRM says now about the last season. He never thought the show would catch up with him:

https://www.buzzfeed.com/alexgurley/george-rr-martin-got-issue

That’s his own damn fault. If he had just hunkered down and written the books, he would have beaten the show.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

ChristianParticipantJune 26, 2021 at 6:58 am #67806

ChristianParticipantJune 26, 2021 at 6:58 am #67806I first heard this term in the old MW Game of Thrones thread. Some of the characters were guaranteed to be there the last season so you knew they would survive whatever came.

At the same time, the possibly biggest draw of Game of Thrones was that some characters who you thought had plot armour just didn’t. For people who didn’t know the book, Ned’s death came entirely unexpectedly and was horrifying because of that. Same goes for the Red Wedding; these characters were killed at a moment when all our instincts were telling us that their plots were building up to something big, that they were absolutely cloaked in plot armour. But that was just GRRM fucking with the reader.

That was the last big one though, it has to be said, and you can’t pull off that kind of thing forever, of course. Some of the heroes have to survive and make it through to the ending – subverting expectations is one thing, but there’s a limit to how much you can piss off your readers.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJune 26, 2021 at 12:57 pm #67838That was the last big one though, it has to be said, and you can’t pull off that kind of thing forever, of course. Some of the heroes have to survive and make it through to the ending – subverting expectations is one thing, but there’s a limit to how much you can piss off your readers.

Martin also mentioned that as well in a sense:

“If you have planned in your book that the butler did it, and then you read on the internet that someone’s figured out that the butler did it, and you suddenly change in midstream that it was the chambermaid who did it, then you screw up the whole book… You have got this foreshadowing early on, and you have got these clues you have planted, now they are dead ends, so you have to introduce new clues, and you are retconning, and it’s a mess.”

For a while Game of Thrones became more of a game in itself than a story. In the way you can almost put together a betting pool on what major character would die every season and that was the appeal rather than what goals the characters accomplished or failed to do in the story. Then it becomes more about finding ways to surprise the audience than actually leading people along the natural development of the narrative.

The initial surprising death of Ned Stark was supported or “foreshadowed” by the deaths of Mycah and Sansa’s wolf Lady. Even the opening scene introducing Ned is an execution that he performs (and he also killed Lady). When Ned dies, it is clear that there were no promises made by the story to the reader other than the characters will face the consequences of their decisions and there are no grey wizards or fairy godparents to make sure everything turns out okay.

At the same time, every outcome will be supported by events and actions preceding them. Ned was essentially his own executioner and every major death early in the story was the natural consequence of the actions of those people that died. Even in minor deaths, usually it was an error or offense committed that led to the death. That wasn’t true by the last season of the show, though.

-

JonParticipantJune 26, 2021 at 6:54 pm #67879

JonParticipantJune 26, 2021 at 6:54 pm #67879Well, there’s something to consider about GoT, and it’s the lenght… because here’s the thing, even GoT had a pattern, but it took longer for it to be revealed because it’s a VERY long story, so that allowed for more suprises than a shorter story would. But by the point of the Red Wedding, or thereabouts, you start seeing the grander scheme of things and at that point you can more easily predict who’s gonna die and who’s gonna make it. But sure, before that it seems like a free for all, but it’s not really.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Al-xParticipantJune 27, 2021 at 6:02 pm #67940

Al-xParticipantJune 27, 2021 at 6:02 pm #67940Bill Maher had an interview with Quentin Tarantino. Both were complaining about the state of movies today saying it is both the pc “virtue signaling” and superhero movies.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/quentin-tarantino-and-bill-maher-whine-about-how-movies-are-too-pc

The thing is imho, we all know better now and some scenes in movies were wrong to begin with even back then. We all cringe now.

I could go on to relate the scene in Animal House where the girl passes out and the guy debates taking advantage of her, or the Nadia scenes in American Pie where she does her thing unknowingly in front of a webcam. Then there is gratuitous nudity just to give a movie a certain edge, or a rape scene,…. and on and on.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJune 27, 2021 at 9:09 pm #67962Still, popular movies and entertainment are not supposed to be instruction books on life or meant to be providing any examples of moral or acceptable behavior, and the material that does have a message is probably only going to reach the people who don’t need the message. People go to the movies or play games to escape – so it makes no sense to expect any moral restrictions or censorship of whatever the creative minds behind the works are trying to sell. The material will appeal to the audience that pays to enjoy it.

Essentially, much of what people see as “PC” is just simply the business. The guys paying for the movies, televisions shows and every other form of entertainment are trying to make sure their very expensive products don’t generate some unexpected bad press. At the same time, the criticisms fly so fast from every unexpected angle – and are so ubiquitous – I’m seeing more of a trend where they just don’t care if anyone gets offended anymore as long as people are buying it.

In the end, it comes down to if the movies and shows are making money, then that means people are going to see them and enjoying them. If they weren’t, then people would stop making them. If anyone is having trouble getting something made, the excuse that it isn’t PC is not convincing. It most likely is a variety of other reasons and at the top of the list is that there aren’t enough people out there willing to pay for it. There are plenty of extremely PC, representative movies with a positive message on diversity and belonging that don’t have anyone going to see them, too. On top of that, it’s just an extreme longshot that anything will get made much less that anyone will go see it if it does. If anything is wrong with show business, it’s that there are just too many people who want to get into it, and not enough ways to make money at it.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

ChristianParticipantJuly 3, 2021 at 7:04 am #68412

ChristianParticipantJuly 3, 2021 at 7:04 am #68412I think Tarantino is probably talking out of his ass, but I’d like to see what he actually said. Daily Beast won’t show it to me if I’m not a paying subscriber though.

Choice quotes maybe, Al?

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 3, 2021 at 7:13 am #68416Tarantino is probably talking out of his ass

![Image - 205416] | You Don't Say? | Know Your Meme](https://i.kym-cdn.com/photos/images/facebook/000/205/416/vampires-kiss.jpg)

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

garjonesKeymasterJuly 3, 2021 at 8:06 am #68423

garjonesKeymasterJuly 3, 2021 at 8:06 am #68423Bill Maher is increasingly an old man shouting at clouds. There’s always some truth in criticisms but his entire shtick is becoming ‘kids today’ in the same way men in their 60s were moaning about his generation in the 1960s and 70s.

He’s another that goes on and on about this so called ‘cancel culture’ and ‘you can’t say anything these days’ when he has his own TV show where he says whatever he thinks and then plugs all the live shows he’s doing at the end.

There are plenty of films of all kinds made every year, he doesn’t have to watch the superhero ones if he doesn’t want to. I am not a huge fan of horror movies, I only like a very few that have maybe an original edge to them, so although hundreds are made every year I don’t bang on about it, I just watch something else. It’s very easy.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

njerryParticipantJuly 3, 2021 at 3:24 pm #68462

njerryParticipantJuly 3, 2021 at 3:24 pm #68462Choice quotes maybe, Al?

I’m not AL, but here’s some:

Tarantino then referenced an incident that occurred at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival, where Once Upon a Time in Hollywood received its premiere. When a New York Times journalist asked Tarantino why he gave Robbie’s Tate such little dialogue, Tarantino became agitated, firing back, “I just reject your hypothesis.”

“I had a situation like that where somebody asked me about something, ‘Well, why didn’t you do this like this,’ and I go, ‘Oh, would you have done that?’ ‘Yes, I would have done that…’ OK, but you never would have written that script, and you never would have made the movie, and thus you never would have been at the Cannes Film Festival in the first place, so it’s a moot argument,” explained Tarantino. “But there has become a thing that’s gone on, especially in this last year, where ideology is more important than art. Ideology trumps art. Ideology trumps individual effort. Ideology trumps good. Ideology trumps entertaining.”

Then Maher added, “There are two kinds of movies: virtue-signalers and superhero movies.”

“Yeah,” Tarantino replied.

That’s about it.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

DavidMParticipant

DavidMParticipant -

Al-xParticipantJuly 3, 2021 at 6:43 pm #68483

Al-xParticipantJuly 3, 2021 at 6:43 pm #68483Here is what Bruce Lee’s daughter had to say about Tarantino and others:

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 3, 2021 at 9:31 pm #68504“I had a situation like that where somebody asked me about something, ‘Well, why didn’t you do this like this,’ and I go, ‘Oh, would you have done that?’ ‘Yes, I would have done that…’ OK, but you never would have written that script, and you never would have made the movie, and thus you never would have been at the Cannes Film Festival in the first place, so it’s a moot argument,” explained Tarantino. “But there has become a thing that’s gone on, especially in this last year, where ideology is more important than art. Ideology trumps art. Ideology trumps individual effort. Ideology trumps good. Ideology trumps entertaining.”

The initial comment makes a lot of sense, but I don’t see the connection to the conclusion that ideology trumps entertainment. Or that anything has been different when it comes to ideology and movies. It’s not like Tarantino movies and the movies he loved are free of ideology.

Though, honestly, I don’t think he necessarily believes it or even means anything about it. Or if he knows what he means. It reads more like the thing people say in interviews to sort of fill space. Same for Maher. It’s something to say rather than saying something.

-

ChristianParticipantJuly 5, 2021 at 6:26 am #68592

ChristianParticipantJuly 5, 2021 at 6:26 am #68592“I had a situation like that where somebody asked me about something, ‘Well, why didn’t you do this like this,’ and I go, ‘Oh, would you have done that?’ ‘Yes, I would have done that…’ OK, but you never would have written that script, and you never would have made the movie, and thus you never would have been at the Cannes Film Festival in the first place, so it’s a moot argument,” explained Tarantino. “But there has become a thing that’s gone on, especially in this last year, where ideology is more important than art. Ideology trumps art. Ideology trumps individual effort. Ideology trumps good. Ideology trumps entertaining.”

I get his point artistically when it comes to the content of his answer to the actual question, but he should stop being a petulant fucking child. Oh, someone dared ask a political question? How terrible, ideology has become more important than art because someone dared to question my massively successful, well-loved-by-critics, Oscar-nominated, many-awards-winning movie at Cannes, where it was also nominated for the Palm d’Or! Woe is me!

Though, honestly, I don’t think he necessarily believes it or even means anything about it. Or if he knows what he means. It reads more like the thing people say in interviews to sort of fill space. Same for Maher. It’s something to say rather than saying something.

Well, I think with both of them it’s something that comes out in this kind of moment because it’s what they’re talking about all the time. Maher especially. Just… ugh. “Virtue-signalling”. I hate that whole term so much. What, so there are a lot of movies in which the good in people triumphs over their worse instincts? What a crazy thing, to have that in the theatres! Man, someone should tell Charlie Chaplin to fuck off with his virtue-signalling speech in The Great Dictator!

There’s always been that kind of movie, and there always will be. But just because Bill Maher apparently hasn’t seen I’m Thinking of Ending Things or Guns Akimbo, that doesn’t mean there’s only two kinds of movie now.But what Maher is really talking about, of course, is that so many movies are making an effort to include previously excluded minorities or shape female roles in such a way that the characters have an agenda of their own. How dare they! When obviously the only movies worth a crap are exclusively about white middle-aged men!

-

This reply was modified 4 years, 5 months ago by

Christian.

Christian.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

This reply was modified 4 years, 5 months ago by

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 5, 2021 at 7:43 pm #68647But what Maher is really talking about, of course, is that so many movies are making an effort to include previously excluded minorities or shape female roles in such a way that the characters have an agenda of their own. How dare they! When obviously the only movies worth a crap are exclusively about white middle-aged men!

On top of that, honestly, it’s not that many movies doing it anyway, and a lot of them that are overt about it don’t perform very well at the box office either. It’s complaining about something that is not really having much of an effect on movies or television. Instead, movies and tee vee have much bigger problems and the amount of attention given to it – especially negatively in the sense that movies are getting too woke – isn’t really justified.

Instead, what’s happening is that the market is contracting for anything that isn’t the dumbest, least exciting or original material available. That’s a bigger problem and it has nothing to do with social justice or diversity initiatives.

It’s like in sports where there is all this controversy over transgender athletes when they represent hardly any portion of the actual number of athletes out there and where they do compete, the athletic associations often are able to successfully integrate them fairly in the competitions. However, the thing that has a much greater effect on competition is doping and you’ll find the same people going nuts over transgender athletes basically shrugging off the effect of steroids or HGH on the same sport.

I mean, Tarantino really should shut up about “virtue signalling” or “ideology” when he’s never really openly addressed his relationship with Harvey Weinstein who turned out to be a much bigger problem in indy filmmaking.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

JRCarterParticipantJuly 6, 2021 at 3:29 am #68670

JRCarterParticipantJuly 6, 2021 at 3:29 am #68670 -

lorcan_nagleKeymasterJuly 6, 2021 at 5:35 am #68671

lorcan_nagleKeymasterJuly 6, 2021 at 5:35 am #68671Will Cancel Culture Lead to the End of Insensitive TV Characters? (Guest Blog)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Betteridge%27s_law_of_headlines

Betteridge’s law of headlines is an adage that states: “Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no.” It is named after Ian Betteridge, a British technology journalist who wrote about it in 2009, although the principle is much older.[1][2] The adage fails to make sense with questions that are more open-ended than strict yes–no questions.[3]

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 6, 2021 at 7:16 am #68674Will Betteridge’s Law Lead To Less Clickbait?

5 users thanked author for this post.

-

ToddParticipantJuly 6, 2021 at 1:17 pm #68690

ToddParticipantJuly 6, 2021 at 1:17 pm #68690Will Cancel Culture Lead to the End of Insensitive TV Characters? (Guest Blog)

That was a terrible “article”. It offered no insight or real explanation.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Al-xParticipantJuly 10, 2021 at 5:52 pm #69214

Al-xParticipantJuly 10, 2021 at 5:52 pm #69214Regarding gratuitous nudity in a movie or cable TV show to give it an edge:

There are actresses who decline it and it is in their contract. One reason is they don’t want perverts to “overuse” the pause button to “you know” to the image. And for the most part it really isn’t necessary.

——

Anyone here to post a rewrite idea to improve a movie or show? We used to do that in MW and the thread would get so long and thought provoking… I have a few ideas and will get it all together when I have time and if there is an interest.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 10, 2021 at 6:56 pm #69221There are actresses who decline it and it is in their contract. One reason is they don’t want perverts to “overuse” the pause button to “you know” to the image. And for the most part it really isn’t necessary.

You’re right, it really isn’t necessary to pause it if you’re quick enough.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Al-xParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 6:22 pm #69256

Al-xParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 6:22 pm #69256 -

JonParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 7:16 pm #69262

JonParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 7:16 pm #69262Oh Buzzfeed, never change… just go away please…

-

Al-xParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 7:53 pm #69266

Al-xParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 7:53 pm #69266Ok boys and girls… rewrite time:

Godfather 3 likes: Such a same Copolla could not pull off a trifecta. What I liked was showing Sonny’s illegitimate son he had when he was banging that bridesmaid in the first movie. Copolla could also have shown the next generation, how Sonny’s, Michael’s and the sister’s kids would have accepted his illegitimate son, maybe a power struggle as to who would succeed Michael, just emphasize them coming of age. Lose the whole Vatican story and Michael’s redemption, maybe bring in an up and coming rival family, and Michael’s last master plan as his last hurrah. Have many wonder if he is too old and still has it in him. And play up the intrigue.

Star Wars Return of the Jedi – The eddy bears saved the day. Redo Han’s rescue from Jabba with a lot less swashbuckling, have Boba Fett still be at large in the movie. Play up the drama more between Luke and Vader and Palpatine’s temptation. Lose the Ewoks and bring in another race of aliens.

Matrix 2 and 3 – Really address Neo’s role in Matrix, and emphasize did he really have a choice or was he still playing out a script. Less action stunts. Mr. Smith as the antichrist figure to Neo’s role was ok, but could have had a better set up. Then again the whole thing of free will was a LOT and the Wachowski’s bit off WAY more than they could chew…

So… These are just three. Any suggestions?

Any more movies or shows you wish they rewrote like in BSG, Trek, Star Wars prequels, (or the Disney movies), Marvel, or whatever?

-

JRCarterParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 11:48 pm #69288

JRCarterParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 11:48 pm #69288Star Wars Return of the Jedi – Lose the Ewoks and bring in another race of aliens.

I remember it was originally gonna be Wookies.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

JonParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 11:54 pm #69290

JonParticipantJuly 11, 2021 at 11:54 pm #69290Matrix 2 and 3 – Really address Neo’s role in Matrix, and emphasize did he really have a choice or was he still playing out a script. Less action stunts. Mr. Smith as the antichrist figure to Neo’s role was ok, but could have had a better set up. Then again the whole thing of free will was a LOT and the Wachowski’s bit off WAY more than they could chew…

Nah, you’re crazy. Yes, they could’ve cut some action pieces out of the movie entirely and shorten the rest and basically make it one movie instead of two bloated parts… but in terms of story and all that, it was good.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 12, 2021 at 6:24 pm #69331Godfather 3 likes: Such a same Copolla could not pull off a trifecta. What I liked was showing Sonny’s illegitimate son he had when he was banging that bridesmaid in the first movie. Copolla could also have shown the next generation, how Sonny’s, Michael’s and the sister’s kids would have accepted his illegitimate son, maybe a power struggle as to who would succeed Michael, just emphasize them coming of age. Lose the whole Vatican story and Michael’s redemption, maybe bring in an up and coming rival family, and Michael’s last master plan as his last hurrah. Have many wonder if he is too old and still has it in him. And play up the intrigue.

Godfather 3 was just ill-concieved. Most of the previous two movies had been based on history to a loose extent, but this one had no connection to reality or believability whatsover (a helicopter strafing a boardroom in the middle of a city?)

Honestly, they could have rejiggered the whole “Mafia assassinated Kennedy” thing to great effect.

Imagine that Michael’s son, rather than being an opera singer, instead was a US senator who opposed the Bay of Pigs invasion and was tough on organized crime and now was in line to be the next President. In the first movie, Don Corleone did not want Michael to be a gangster and instead wanted him to be a real bigshot – a senator or big time CEO. Michael said “we’ll get there, pop.” So naturally, that would be what he wanted for his son.

Then, his son does become a legitimate power but he threatens Michael’s “family” the La Cosa Nostra. So Michael has to make a choice – his son or his family – and it leads to an assassination of Senator Anthony Adams (he takes his mother’s surname) while he is on the campaign for president.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 12:42 am #69359One point about Star Wars… how does Princess Leia know that Obi-Wan goes by Ben Kenobi (a crappy alias, you have to admit)? Had they ever met?

As far as my headache with the Matrix – even though it and X-men were influential on the current crop of colorful underwear adventures, the sequels always felt somewhat off-point compared to the original. Essentially, imagine if you’re reading the Bible and Jesus is anointed the Messiah and instead of leading a movement, he becomes John the Baptist’s sidekick and goes on raids against the Romans with Mary Magdalene and a team of quirky zealots.

At then end of the movie, Neo says this:

Well, nothing changed and Neo wasn’t showing any of “these people” anything of what that promised. The people who were “trapped in the Matrix” were completely ignored in the sequels when the original ending promised a kind of disruption of the simulation that the machines could not control.

It is in some ways what I don’t like in superhero movies in that the people the heroes are saving are non-entities or NPC’s really in the movies.

I look back at the old shows like Maverick, the Lone Ranger, Have Gun Will Travel, Superman, etc. and the story of the people the hero encounters and helps really is the story of the show. We may learn things about the hero, but really the elements of the story are what he walks into and he becomes a part of their story rather than they become a part of his.

What was promised was Neo freeing people and forming a movement, but what we got was just a collection of heist movie tropes and battle scenes with Neo being a reactive hero rather than driving the action.

-

JRCarterParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 12:51 am #69362

JRCarterParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 12:51 am #69362I’ve got a challenge: make The Room a good movie.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 12:52 am #69363It already is a good movie.

Seriously, though, I heard that originally, Tommy’s character was going to secretly be a thousand year old supernatural being who was trying to fit in with a culture he did not really understand.

Honestly… maybe that really is the story of the movie.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 13, 2021 at 6:11 am #69386What was promised was Neo freeing people and forming a movement, but what we got was just a collection of heist movie tropes and battle scenes with Neo being a reactive hero rather than driving the action.

It’s implied that some of that stuff has happened off-screen (and we see a bit of it in the Animatrix shorts), especially with the kid who is in the sequels.

But yeah, it definitely feels like a case of the second and third movies not delivering on what that final scene in the first one promised. It’s like… I want to see that movie.

-

lorcan_nagleKeymasterJuly 13, 2021 at 6:42 am #69390

lorcan_nagleKeymasterJuly 13, 2021 at 6:42 am #69390I’m gonna just shamelessly promote a friend’s video about the matrix sequels:

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

ChristianParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 7:54 am #69393

ChristianParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 7:54 am #69393What was promised was Neo freeing people and forming a movement, but what we got was just a collection of heist movie tropes and battle scenes with Neo being a reactive hero rather than driving the action.

Yeah, that’s it in a nutshell.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

JonParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 9:01 am #69402

JonParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 9:01 am #69402What was promised was Neo freeing people and forming a movement,

Nah, that’s too simplistic.

Plus the sequels aren’t only about the humans and Neo, there’s a big, big part that pertains the machines themselves, as you can gather from the Oracle’s plot. Making it about a bunch of humans banding against the machines is a bit boring, tbh… might as well call it Terminator.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 11:09 am #69411I read an interesting dissection of Ghostbusters and Jurassic Park on the MensLib subreddit. I will quote the post below, but since it’s referring to a quote from another post, I’ll post that small one first. For context:

Another MensLibber and I read bell hooks’s The Will To Change together, and we both flagged this quote from Olga Silverstein:

“feminist masculinity would have as its chief constituents integrity, self-love, emotional awareness, assertiveness, and relational skill, including the capacity to be empathic, autonomous, and connected.”

With respect to integrity, what she means is that traditional masculinity tells us to ignore or excise the ‘feminine’ aspects of our personality, so not allowing us to be whole persons. ‘Emotional awareness’ and ’empathy’ are in contrast to the reserved and stoic nature of traditional masculinity, while ‘assertiveness’ replaces the need for dominance in traditional masculinity.

[Edit: given how the word ‘traits’ is being used below, let me point out that feminism doesn’t see these as ‘traits’ in the sense of intrinsic or genetic traits (i.e. biological). Rather, these are learned behaviors and skills, as ‘traditional masculinity’ is also a set of learned behaviors and skills. So one way to think about the quote is as ideas for how we might teach boys to be men, absent patriarchal dominance.]

And here’s the promised dissection of Ghostbusters and Jurassic Park:

So [the above post] with a quote from bell hooks got me thinking about putting down something that’s been floating around in my mind. This past fall, we did an outdoor home theater for social distanced Halloween moving viewing, and I watched Ghostbusters for the first time in years. I was struck, perhaps unsurprisingly given being released during the peak of Reaganism, of how conservative it was in its worldview, broadly, but how feminism really serves as as the villain. More recently, I was shocked to learn that my wife had never seen Jurassic Park (I mean, seriously, if you are in your 30s and haven’t seen this, were you living under a rock as a kid?!) Similarly, I was struck by how (more overtly) feminism was central to the plot. The conclusions couldn’t be more different, however, with Ghostbusters doubling down on traditional masculinity, while Jurassic Park encourages evolution of men. Allow me to elaborate – and I apologize in advance if I mistake some details as I’m trying to write this quickly during my kid’s nap.

GHOSTBUSTERS AND INSECURE PROJECTION

I was surprised to learn, when my suspicions of Ghostbusters political undertones led me to doing some googling on the subject, that the movie is well regarded in conservative to libertarian-leaning circles. There are some very obvious red meat quotes for this crowd, with the early jab at academics from Dr. Venkman:

“Personally, I liked the university. They gave us money and facilities, we didn’t have to produce anything! You’ve never been out of college! You don’t know what it’s like out there! I’ve WORKED in the private sector. They expect *results*.”

Ultimately, too, the initially captured ghosts are released back by the combination of bureaucratic malfeasance and environmentalism at the hands of the “dickless” (as Ray insults the agency goon) Environmental Protection Agency. The mayor is initially no help, until being pitched with an cynical and reductionist view of politics about being interested only in votes.

But the point of this essay isn’t the broad conservative viewpoint espoused – I only reference this to reinforce that there is an ideology, intentional or not, to Ghostbusters. More fundamentally, the roles of Dana and Louis project significant insecurity of the consequences of growing women’s liberation.

Venkman is undeniably the central protagonist. Despite being a Dr., he acts more like a “gameshow host”. He is no abstract theoretician, but a very-hands on charismatic speaker. He is insistent, cocky. He openly mocks Egon as an egghead scientist despite the fact that their whole enterprise depends on his and Ray’s scientific work. He’s an archetypal fulfillment of many traditionally masculine ideals.

On the other hand, we have Louis. Diminutive in stature, which is strongly emphasized by his “flirting” at his awkward client party, also insistent with women like his neighbor Dana, but in a creepy “Nice Guy” kind of way. He’s a “nerd” – the fact that he likes numbers is the butt of more than a few jokes. He’s a necessary punching bag because this kind of man – a white collar professional – is ascendant in America in the 1980s. Rest assured, blue collar man, these new rich guys are dweebs!

Dana, too, fulfills a projection of insecurity of an emerging class – the independent woman. She’s middle-ageish, single, urban-dwelling and presumably career-oriented woman living in NYC, a sort of boogeywoman for working class male insecurity at the time. While she is put off by Louis, she somehow succumbs to Venkman’s relentless, pushy insistence and agrees to a date. Upon showing up for the date, we see Venkman’s real-time confrontation with the Madonna/whore complex. He’s drawn into the now-possessed Dana’s sexual aggressiveness, but stand-offish at the end

Dana: “I want you inside me.”

Venkman: “Go ahead! No, I can’t. It sounds like you’ve got at least two or three people in there already.”

A joke about her possession? Or a projection of the idea that feminism = sexual promiscuity that ruins women for men? You decide!

This flirtation with gender roles gets even stronger as the Gatekeeper and Keymaster emerge (note the sexual imagery of inserting the key into a lock!). These two – the white collar nerd and professional single woman cannot be paired – it would be doom for all! And when they do, the product is Gozer, who selects a highly androgynous, Bowie-esque female avatar. Gozer’s appearance does not escape Ray who instructs his companions to “aim for the flat top”.

To defeat this demon of androgyny, the Ghostbusters perform a rather homoerotic act of crossing the streams. The phallic nature of this act cannot be denied – upon initially encountering Gozer, the Ghostbusters “grab their sticks, heat them up, [and] make them hard”, and later these hard sticks’ streams are crossed to vanquish the marshmallow man, covering everyone in a thick, white goo (yuck!).

Message received: fear not, male solidarity in the face of changing gender norms is the only solution. Do not be a Louis or an Egon. Do not be an environmentalist, a government bureaucrat, a scientist or an academic. Be a smooth-talking everyman, stick to your womanizing ways and we’ll defeat the possessive demon of feminism.

JURASSIC CONTRAST

Jurassic Park as a feminist statement is quite clear – Dr. Sattler is an undeniable badass, as is the young Lex. There are a handful of explicit references to gender/feminism:

Dr. Ian Malcolm: “God creates dinosaurs, God destroys dinosaurs. God creates Man, man destroys God. Man creates dinosaurs”

Dr. Ellie Sattler: “Dinosaurs eat man….. Woman inherits the earth”

Or when Hammond halfheartedly protests Dr. Sattler’s volunteering to turn the power back on because he’s a…and she’s a…

But beyond these superficial themes, there’s a deeper thing going on, which Dr. Grant is the center of. Most of the men embody traditional and toxic masculine traits. Dr. Malcolm is a flirtatious rock star and bad husband (a pretty good stand-in for Venkman, if you ask me). Hammond is focused solely on technological achievement and not morality. The lawyer is immensely greedy, abandoning the vulnerable at first chance, and Nedry a greedy, anti-social nerd with a chip on his shoulder. Muldoon is calm, cool and collected, but violent by nature, and more than a bit cocky of his ability to dominate nature. Sattler calls out Hammond’s behavior directly in the visitors center after she makes her way back, when he’s eating ice cream to console himself, but her message goes unheeded:Dr. Ellie Sattler : But you can’t think your way through this, John. You have to feel it.

John Hammond : You’re right. You’re absolutely right. Hiring Nedry was a mistake, that’s obvious. We’re over-dependent on automation. I can see that now. Now, the next time, everything is correctible…

Dr. Ellie Sattler : John…

John Hammond : Creation is an act of sheer will. Next time it’ll be flawless.

Underpinning all of this is masculine insecurity. Jurassic Park is evidence that we’ve reached sufficient technological sophistication that men are no longer “necessary”. An entirely female island (well, kind of…) is genetically engineered without need of male sperm. Metaphorically, women have reached a point where the traditional man is no longer necessary. They are their own, independent beings that don’t need to be subservient to men to survive. The traditionally masculine men on the island are themselves dinosaurs on the precipice of extinction.

The only man that fully breaks the mold is Dr. Grant. He clearly dislikes children, a rejection not of fatherhood per se, but rather the empathy and emotional connection it requires to be a caretaker which is not consistent with traditional masculinity. Yet, it is in his nature not to follow the designated paths assigned to him. Twice he is the instigator to break the “rides” he is on – once in the visitor center rotating theater, and a second time by climbing out of the car when seeing a sick triceratops. When the shit hits the fan, he finds his place as a protector, not saving Lex and Tim simply through acts of physicality, but because he connects with them emotionally. He lifts their spirits with jokes, he encourages them when they are afraid.

Dr. Grant undergoes a metaphorical evolution of his own, which is prefaced in the tree with Lex:

Lex : What are you and Ellie gonna do now if you don’t have to pick up dinosaur bones anymore?

Dr. Alan Grant : I don’t know. I guess… I guess we’ll just have to evolve too.

Ellie is mentioned here, too, but it’s hard not to read this as “now that you are an unnecessary fossil, yourself, what are you going to do?” Upon safely rescuing Lex and Tim, Dr. Grant looks out the helicopter window, reminded that dinosaurs evolved into birds, and we cut back to a shot of Grant, wings spread over the children, and an approving, knowing look from Dr. Sattler that Grant has evolved into a “bird” of his own.

To me, it is critical that this isn’t a simple evolution that Dr. Grant is ready to be a father. It would be a rather constrained view of evolved masculinity that we only find purpose as fathers. Rather, Dr. Grant is caring for someone else simply because they are vulnerable. His paternal role is not to dominate them, but to support their growth and emotional health. A lesson we can all learn as men. It

A CONTRAST IN MESSAGING

It seems the message in Jurassic Park is too clear to deny it wasn’t a top-of-mind metaphor for the writer(s), which is a bit surprising given that Michael Crichton’s politics are a bit of a mixed bag. Yet Ghostbusters writers Aykroyd, Ramis and Moranis’ politics are unclear, it seems they were channeling popular culture sentiments of the time – insecurity about cultural change, anti-government sentiments, blue-collar primacy, etc. And in doing such, I suspect that a lot of the meaning of Ghostbusters was a projection of cultural insecurity about feminism, rather than an intentional theme. If it were intentional, it seems the only way you would consciously write a conclusion that were a laughably homoerotic statement of masculine solidarity were if you were very subtly satirizing the political views of the time. Yet we have little evidence to suggest satire here.

Written just a few years apart, we see two highly contrasting views related to insecurities about the rise of feminism and successful, independent women. The first, is Ghostbusters, which seems to suggest not only zero necessity for self reflection or evolution, but in fact a doubling down on gender roles. The latter, in the case of Jurassic Park encourages an “evolve or die” mentality for men. We are walking dinosaurs, our traditional masculine roles of dominance are no longer relevant, so what does that leave us? Stop solely thinking our way through things, stop our tendency towards achievement without consideration for consequence, and instead reconnect with our emotions and our caretaking nature. Be a bird, not a dinosaur. Don’t accept the path your vehicle is on, jump out the door and go see the Triceratops!

I welcome your thoughts or additions, and hope this isn’t a pointless navel-gazing about pop culture, but instead an opportunity to think about how art and culture reflect (or challenge) the values we espouse here.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 13, 2021 at 11:13 am #69413Dana: “I want you inside me.” Venkman: “Go ahead! No, I can’t. It sounds like you’ve got at least two or three people in there already.” A joke about her possession? Or a projection of the idea that feminism = sexual promiscuity that ruins women for men? You decide!

It’s the first one.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

DavidMParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 11:16 am #69414

DavidMParticipantJuly 13, 2021 at 11:16 am #69414I look back at the old shows like Maverick, the Lone Ranger, Have Gun Will Travel, Superman, etc. and the story of the people the hero encounters and helps really is the story of the show. We may learn things about the hero, but really the elements of the story are what he walks into and he becomes a part of their story rather than they become a part of his.

This is where modern sequels or on-going series fail. They’ve told the hero’s story, and then they’re stuck with what to tell next. They either reset (reboot) and tell the same story again, or they raise the stakes x10 so you think you’re getting something new, but they still really tell the same story again.

There are (generally old) shows where you spend half of it watching the supporting cast before the nominal “protagonist” even appears. I was thinking about this watching a Colombo re-run recently. 40 minutes into a 2-hours film and we’re still with the murderer. Columbo comes in almost as an afterthought in his own show — but once he does come in, he instantly commands every scene, and he look better because we’ve just spent 40 minutes learning how clever his adversary is.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 11:26 am #69415Dana: “I want you inside me.” Venkman: “Go ahead! No, I can’t. It sounds like you’ve got at least two or three people in there already.” A joke about her possession? Or a projection of the idea that feminism = sexual promiscuity that ruins women for men? You decide!

It’s the first one.

It’s definitely the first, but I believe the second part is there too.

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 13, 2021 at 12:14 pm #69418Yeah, I mean to be serious all of that stuff is barely even subtext in both those movies. We’re meant to be amused by Venkman being suddenly intimidated by a sexually-confident Dana as it turns the tables of their earlier encounter. That’s the whole point.

Rather than promoting ultra-traditional gender roles and trying to bolster them though I think Ghostbusters goes somewhere a bit more in the middle. The three main Ghostbusters themselves are shown as geeky, childlike and sleazy respectively, making fun of those male traits (none of them is shown to be really successful with women, even if Ray does get a blowjob from a ghost). It’s mocking them just as much as it’s mocking Tully for his nerdy impotence.

And really, the fact that both Zuul and Gozer manifest predominantly as female characters has to count for something. The females are where the real power is, even if the Ghostbusters push back against that.

It’s kind of weird that whole analysis taking the film so seriously and saying there’s no evidence of satirical intent in Ghostbusters. Of course there is! The leads are as much the butt of the jokes as they are the heroes of the piece.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 13, 2021 at 12:15 pm #69419geeky, childlike and sleazy

There’s a new Seven Dwarfs movie in this.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 4:50 pm #69438It’s the first one.

It’s the general headache of film analysis or any criticism that seeks to find messages in stories other than the actual story itself which is a piece of fiction. Whatever “message” or “meaning” the analysis claims to discover is always going to be a projection of the analyst. It is not the message or meaning of the movie – it’s the analyst’s message.

In 300, the Spartans could represent the xenophobic isolationist and militant American culture faced with a terrifying threat from the Middle East. This was 2006 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were still hot. The apparent propaganda push seemed pretty obvious.

However, as many pointed out, the Spartans could equally represent a small group of insurgents facing the overwhelming power of a massive and advanced cosmopolitan and decadent imperial invasion force – essentially they could just as easily be symbols of the Taliban or Al Qaeda.

When all we can really say is that they were entirely fictional characters in a story taken from a comic book that adapted a legend that was already completely divorced from even any historical facts. There is no definite interpretation and fiction in general has nothing substantial to say about reality.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 7:14 pm #69449The females are where the real power is

And the real evil. Only men can defeat them.

It’s the general headache of film analysis or any criticism that seeks to find messages in stories other than the actual story itself

Ah, yes. The age old adage that any story can’t have a message or subtext that is bigger than the story. Like the story of the rabbit and the turtle, which is about a turtle and a rabbit racing, nothing else. Any ideas about morality in any of the classic fables is derived purely on the whims of the person the story is told to. As it ever was.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 13, 2021 at 8:04 pm #69456I think we’re all able to look at an analysis like this and decide whether we think a subtext being described arises naturally or is being forced. And that’s obviously a subjective decision.

For what it’s worth I think the stuff about Jurassic Park is all fairly solid and clear when you watch the movie – and there’s lots more than is mentioned in what you pasted above.

But to me (subjectively!) some of the Ghostbusters stuff feels like forcing a reading that you want by picking and choosing pieces in isolation, rather than seeing what naturally grows out of the film as a whole.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 8:13 pm #69459I think we’re all able to look at an analysis like this and decide whether we think a subtext being described arises naturally or is being forced. And that’s obviously a subjective decision.

Hard agree!

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 13, 2021 at 10:44 pm #69465Ah, yes. The age old adage that any story can’t have a message or subtext that is bigger than the story. Like the story of the rabbit and the turtle, which is about a turtle and a rabbit racing, nothing else. Any ideas about morality in any of the classic fables is derived purely on the whims of the person the story is told to. As it ever was.

In the end, it always is. Take a look at the story of the tortoise and the hare since you mention it. The “moral” of the story is usually written as “slow and steady wins the race.” However, even children know that is nonsense. If the hare had simply taken a nap after the race, it would not have mattered how steadily the tortoise plodded along, it never would have won. Depending upon your opponent to be lazy and stupid is a poor strategy.

Sometimes, the moral is written as “victory does not always go to the swift” but that simply points out the uselessness of the moral. Not “always”… but most of the time really. Any kid who heard that parable would still pick the hare over the tortoise in a relay race. The moral is part of the form of the fable or parable or even many modern fairy tales, but in the same way a punchline is part of a joke. Not all stories – not most stories – require a moral, and even those that have one require it only in a formal sense — not as something that can really be applied in any practical way.

However, the moral is not the subtext and the subtext is not the interpretation. If I told you the “real meaning” of the tortoise and the hare was that it is meant to teach people not to take pride in, feel ashamed of and suppress their individual talent, naturally, someone could tell me that is simply supposition and they’d be right.

That interpretation is simply a reaction to the story and it is neither right nor wrong, but it is not an innate part of the story, the author’s intent or any universal reaction to it.

It’s not subtext either.

In Chinatown, which most people have probably seen, Jake Gittes discovers that the Mrs. Mulwray that hired him to prove her husband Hollis Mulwray was having affair was an imposter when the real Evelyn Mulwray shows up in his office and threatens to sue him for slander and any other number if invasion of privacy violations. Jake then pursues the case to find out who set him up and repair his reputation.

That’s the text of the story. The subtext is that he pursues the case because he’s attracted to Evelyn and what drives him isn’t just a need to get even with those who used him but he’s falling in love with her. The subtext are things the audience knows that the characters do not that reveal the actual reasons and motives behind their actions in the context of the story. When Hollis Mulwray is murdered, Jake has no practical need to continue his investigation. He’s not part of the story anymore, but he has a need to continue pursuing Evelyn and he uses the investigation as the excuse.

Chinatown does have a moral, naturally, and it’s that the rich can get away with anything, but that is still in the context of the story. It’s when someone tries to give it some kind of specific interpretation – a Marxist one such as Noah Cross is rapacious capitalism and when he raped his daughter it represented the way capitalism victimizes future generations, for example, that it becomes divorced from the story and becomes supposition – an individual reaction to it, and not an inherent part of it.

-

ChristianParticipantJuly 14, 2021 at 6:56 am #69484

ChristianParticipantJuly 14, 2021 at 6:56 am #69484This flirtation with gender roles gets even stronger as the Gatekeeper and Keymaster emerge (note the sexual imagery of inserting the key into a lock!). These two – the white collar nerd and professional single woman cannot be paired – it would be doom for all! And when they do, the product is Gozer, who selects a highly androgynous, Bowie-esque female avatar. Gozer’s appearance does not escape Ray who instructs his companions to “aim for the flat top”.

To defeat this demon of androgyny, the Ghostbusters perform a rather homoerotic act of crossing the streams. The phallic nature of this act cannot be denied – upon initially encountering Gozer, the Ghostbusters “grab their sticks, heat them up, [and] make them hard”, and later these hard sticks’ streams are crossed to vanquish the marshmallow man, covering everyone in a thick, white goo (yuck!).

This is awesome!!!

It’s the general headache of film analysis or any criticism that seeks to find messages in stories other than the actual story itself which is a piece of fiction. Whatever “message” or “meaning” the analysis claims to discover is always going to be a projection of the analyst. It is not the message or meaning of the movie – it’s the analyst’s message.

(Note of warning: We’re headed towards Death of the Author territory here.)

Your stance presupposes that there is something like an “actual story” or an “actual message” of the text (or the “author’s intention” and “universal reaction”), and that the analyst is trying to uncover that, but getting it wrong.

That’s not the point though, or at least not of this form of critical reading done well. There is no “actual story”, there are as many versions of it as there are readers, and while the biographical author who wrote it is one of the most competent readers of that story, they are sure to have been influenced by a number of cultural and psychological aspects at the time of writing that they maybe aren’t even aware of.

The kind of analyis Anders posted is an approach that tries to uncover some of those influencing factors, but it’s a misunderstanding of this kind of analysis if you see it as trying to construct “the true message” behind the movie, and then misinterpreting it. That’s not the point, it’s looking at a work through a different lense and seeing if you can in this way learn more about the work and the context in which it was created. It isn’t about rivalling interpretations, but about multiple ones that can all be correct. This does not, however, mean that all readings are equally valid and that meaning is arbitrary, as you can and should analyse not only the specific system of signs that is the work but also how it was influenced by the surrounding context of signs that is the culture, society and their specific language (the discourse) of the time. Said analysis can then be seen as having value because it is enlightening when it comes to the work or society, or it can be rejected as being un-convincing.

(This is in a very sketchy way the basic idea of post-structuralism/discourse analysis.)

2 users thanked author for this post.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 14, 2021 at 8:47 am #69495(Note of warning: We’re headed towards Death of the Author territory here.)

It was only a matter of time.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Dave

ModeratorJuly 14, 2021 at 8:51 am #69496This does not, however, mean that all readings are equally valid and that meaning is arbitrary, as you can and should analyse not only the specific system of signs that is the work but also how it was influenced by the surrounding context of signs that is the culture, society and their specific language (the discourse) of the time. Said analysis can then be seen as having value because it is enlightening when it comes to the work or society, or it can be rejected as being un-convincing.

This is the crux of it for me.

And I think that “of the time” is possibly the most important part of that. We see a lot of these analyses that are determined to re-interpret old works through a lens of relatively recent cultural preoccupations. Which is fine as an exercise but I think (like Johnny says) often ends up telling you more about the author than the work itself.

Which is of course a big part of the intention in the solipsistic social media age where everyone wants to have a “hot take”.

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

DavidMParticipantJuly 14, 2021 at 9:21 am #69501

DavidMParticipantJuly 14, 2021 at 9:21 am #69501(Note of warning: We’re headed towards Death of the Author territory here.)

It was only a matter of time.

After all, death is the only certainty in life.

(Not taxes, as any modern multi-national will attest.)

1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 14, 2021 at 2:39 pm #69509Your stance presupposes that there is something like an “actual story” or an “actual message” of the text (or the “author’s intention” and “universal reaction”), and that the analyst is trying to uncover that, but getting it wrong.

I generally agree but you’ve misinterpreted what I mean by “actual story.” ;)

What I mean is the actual experience of an individual viewing or participating in the physical medium – not what the author intended or the conceptual text, but the experience of enjoying a piece of fiction or artwork. Obviously, a Florentine viewing Michelangelo’s David in 1502 would have an entirely different perspective emotionally and intellectually than anyone seeing it today. No matter what Michelangelo intended or what the overseers of the cathedral intended for him to intend, that would not matter today and depending on if the person was noble or a peasant, it probably meant many different things even in the time it was sculpted and first displayed.

However, there are general specific details that people can agree upon when it comes to works of fiction. In Hamlet, every can agree on the events depicted in the scenes. On the other hand, people can disagree on surrounding motives and subtext for the reasons underlying the events. For example, when Hamlet puts on the play-within-a-play “The Murder of Gonzaga,” King Cladius’ reaction to it is taken as evidence by Hamlet that his uncle is guilty of the murder of his father, the previous King Hamlet.

On the other hand, others would point out that in the play Hamlet puts on, it is the story of a nephew who kills his uncle to take his place. So, is Claudius’ reaction motivated because he believes Hamlet – who’s been intentionally acting insane – is now planning to kill him for the throne and not because he suspects him of his brother’s murder? Is Hamlet’s assumption that this proves Claudius is guilty in error?

In the end, though, I like fan theories. There is a really fun theory that in PUNCH DRUNK LOVE, Barry is actually Clark Kent learning to be Superman. There are a lot of clue and Richard Donner’s Superman is one of Paul Thomas Anderson’s favorite movies, but in the end it is just fun speculation and there is no reason to believe that it had anything to do with the making of the movie any more than there is any reason to believe that Jar Jar Binks was originally intended to be a secret Sith Lord (still it is fun).

However, even if a movie or story (like almost all of Dickens’ novels) include a moral message, I don’t think it is revealing any sort of truth. Fiction is an enjoyable escape and often people will claim that a book “can change your life” (usually people invested in the business). Nevertheless, I feel like people simply find what they want to in it. Like reading the Bible – you can pretty much find anything in it to justify anything you already believe – an atheist can find all the evidence they need from the Bible just by reading it with their preconceived view in mind.

In CITIZEN KANE, the moral could be summed up as “wealth does not lead to happiness.” Is that really true or does it just make people who are not wealthy feel good for a little while? Certainly a lot of people who sell that moral get rich doing so.

I do believe there is value in pointing out how narrative fiction misleads – especially how it is used in advertising and politics. The amount of cigarettes, alcohol, cars and clothes sold due to what people see in movies or on television certainly indicates they have an effect, but it’s not the moral of the story that has that effect on people and, often, those morals are not worth learning.

-

ChristianParticipantJuly 14, 2021 at 7:13 pm #69540

ChristianParticipantJuly 14, 2021 at 7:13 pm #69540I generally agree but you’ve misinterpreted what I mean by “actual story.” ;)

Fair enough, we’re in total agreement, then! :)

Love the Hamlet example.However, even if a movie or story (like almost all of Dickens’ novels) include a moral message, I don’t think it is revealing any sort of truth.

Well, for one thing moral messages are often not conducive to literary quality. Dickens is a bit of an exception there.

When it comes to truths, though, I mean… it depends on how you define “truth”. I don’t know about a single piece of art transforming anyone’s life, but I do think that literature can deliver an understanding of human nature or of ideas in a way that makes it important to us.1 user thanked author for this post.

-

Al-xParticipant

Al-xParticipant -

Anonymous

InactiveJuly 14, 2021 at 9:10 pm #69557Well, for one thing moral messages are often not conducive to literary quality. Dickens is a bit of an exception there. When it comes to truths, though, I mean… it depends on how you define “truth”. I don’t know about a single piece of art transforming anyone’s life, but I do think that literature can deliver an understanding of human nature or of ideas in a way that makes it important to us.

I find that as well. For example, reading Chekhov gives me a nice understanding of the lives of peasants and the class system in 19th century Tsarist Russia. Very important to my life.

I think people do read books to get out of their own lives and into someone else’s (though usually that other person really has no relation to reality – and that’s the appeal) and there is a sense that it is “expanding” the consciousness, but I also think that is probably exaggerated (to sell more books, or movies, or television shows that in turn sell more crap to the viewers). I suspect that the real appeal of entertainment is similar to the appeal of alcohol to an alcoholic. It provides temporary relief to the everyday problems people want to put off as much as possible. It may be possible that people who don’t particularly feel any desire to read or see movies, attend plays or spend any time with fiction or media are actually more sane the majority of the population that is enamored of all these distractions. Or that enthusiasm for fiction indicates a strong disappointment or anxiety with real life.

Fiction – even dark depressing fiction – provides a design and structure that real life does not have, and if it reinforces the notions one already possesses, all the better. It’s not like some German in the 30’s read MEIN KAMPF and was suddenly convinced out of nowhere that “of course! It’s the Jews! It’s always been the Jews!” The book gave people who already were in line with that thinking a structure for it, but, then again, while it was probably widely published and purchased, I can’t believe many Germans actually read the whole damn thing.

Plato and Aristotle both had differing views on the uses and effects of poetry (fiction) and drama. Plato thought it promoted immoral behavior, but at the same time he proposed that there should be a state-sanctioned mythology to create a stable class system in society (The Republic). Aristotle agreed that drama had no direct positive effect on society as far as promoting good behavior, but he thought it was a way of expressing destructive emotions that if left repressed would eventually lead to social discord. “The theatre is a safe place for dangerous things.” Censors should be required to have that over the door before they start cutting all the “disturbing content.”

His theory of catharsis is based on the old idea of the scapegoat. Tragedy means “goat song” and in the ancient world there was the practice of sacrificing one goat to the gods and then taking another goat, ascribing to it all the evil spirits of the village and then driving it out into the wilderness. The latter goat was the “scapegoat” (from escape), and the tragic hero often represents the same thing. When the hero dies or falls (driven out of the city), then evils troubling the community are lifted. Oedipus’ fall lifts the plague from Thebes. Macbeth’s death lifts the kingdom from tyranny. Hamlet dies and makes way for Fortinbras who is often left out of many productions, but it is important to note that Hamlet himself admires Fortinbras for having the confidence and boldness of action that he himself lacks.

Comedy also has something of the same effect but I find it darker. Ironically, in tragedy, there is the possibility of happiness at the end after the fall of the hero. However, comedy holds up the hilarious contradictions of life, personality and society and even though everyone laughs at how ridiculous it all is, it remains ridiculous once the curtain closes only now you can’t laugh at it any more.

Some primatologists and zoologists believe laughter is related to fear. Chimps will play practical jokes on each other – basically jumping out and yelling “boo!” and will laugh when someone in their pack takes a fall just like we do. Essentially, the laugh begins as a scream (“oh shit, it’s a lion! Ah!”) then dribbles out as a laugh when they realize something they thought was serious was not (“oh, it’s just Bing again! Ha ha!”). So it is bound up in releasing fear and, in humans, anxiety.

Stephen King suspected that horror was effective when your subconscious mind would look at the supernatural or impossible nature of the horror – ghosts, demons, monsters – and then say “you know, if you just changed it here and here, this is real.” Uncontrollable screaming and laughing is a sign of insanity, and it may just be that the popularity of entertainment is due to the fact that people are keeping all that madness tightly reined in for a great part of their daily lives.

-

ChristianParticipantJuly 15, 2021 at 7:14 am #69590

ChristianParticipantJuly 15, 2021 at 7:14 am #69590I find that as well. For example, reading Chekhov gives me a nice understanding of the lives of peasants and the class system in 19th century Tsarist Russia. Very important to my life.

Well, for one thing you could argue that an understanding of the class system in 19th century Tsarist Russia is important to your life, or to anyone’s really. It’s important to how the modern world came about and deepens our understanding of how the world works. More importantly, finding out how it was to live in systems different from our own makes us aware that the way the world is right now, for us, is not the way it always has to be; that people have lived in different circumstances and that those circumstances can change. Understanding and feeling for those people in 19th century Russia also means that you can understand and feel for anybody anywhere, and I think that’s one of the most important things that literature can do.